Party primaries for the 2023 presidential election in Nigeria have now been concluded. However, the outcome is somewhat disequilibrating: it has thrown up two opposing juggernauts in each arm of the governing duopoly, APC and PDP, whilst setting up a dynamic for a viable – though not yet formidable – Third Force from the stack of fringe parties. The situation could create an ambiguous ballot outcome, suggesting the need for electoral alliances that would produce a clear winner, and a system-preserving outcome, from the election.

By Chudi Okoye

It is quite possible that no single political party will win a clear majority of votes in the first ballot of the upcoming 2023 presidential election in Nigeria.

Let’s be clear: This is not a firm prediction that one is making – not this early in the presidential election cycle. We are nine months out to the election, and this is a really long time in Nigeria’s frenetic democracy. No; this is rather an abductive (i.e., analytic but tentative, speculative but not improbable) hypothesis that one is proposing based on current observations and historical analysis.

It is quite a tall order for any political party to meet the constitutional requirements for ballot victory in a presidential election. The constitution requires a majority of the national votes and a minimum of 25% in at least two-thirds (i.e. in 24) of the 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Abuja. This is a hurdle that either arm of the governing duopoly – All Progressives Congress (APC) and Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) – might find hard to cross in the coming presidential poll. Certainly, the duopoly maintains a strong hold on the institutions of power in Nigeria: it controls 95.4% of Senate seats; 96.1% of House Representatives seats; 97.2% of governorships; and 93.5% of state assembly memberships – all these, in addition to controlling the presidency. Still, although one arm of the duopoly will likely win the upcoming presidential election, the prospect is not without some hazard.

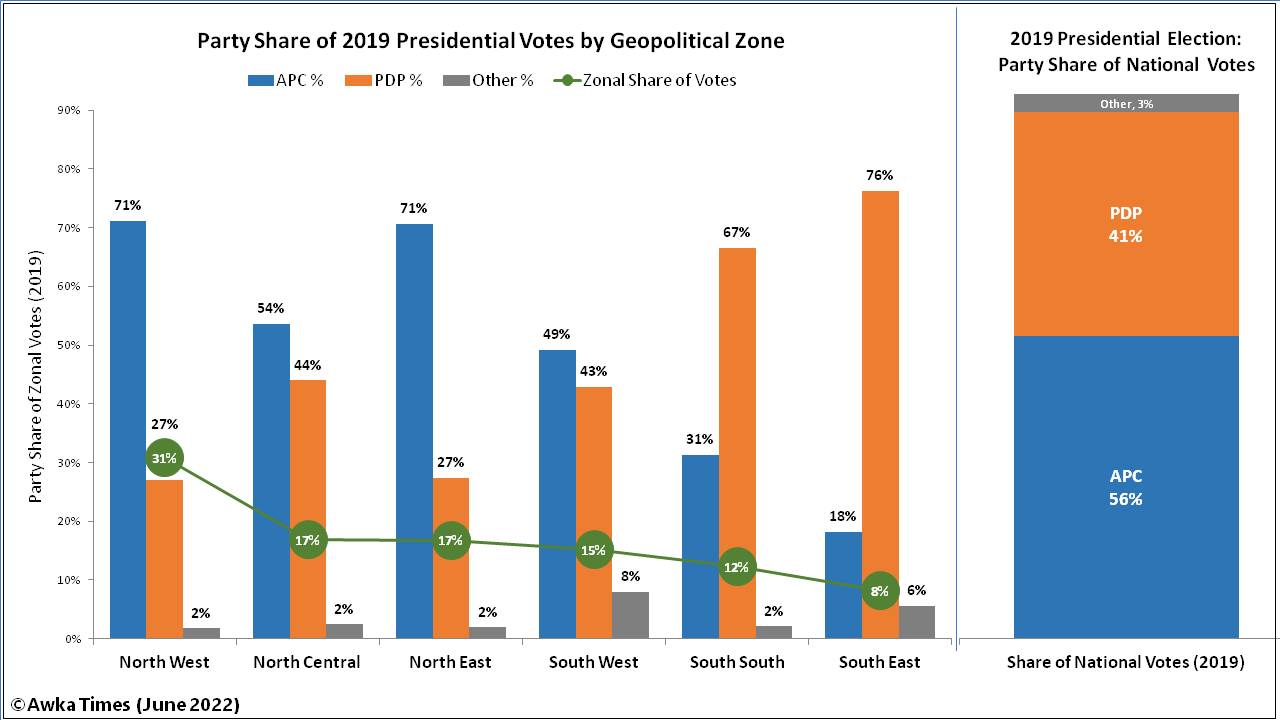

On paper, the federal ruling party, APC, with its advantage of incumbency, should not have any difficulty meeting the constitutional threshold. The party secured about 55.6% of the national votes and over 25% of the votes cast in 33 states and Abuja in the 2019 presidential election. However, APC is unquestionably damaged by its seven-year governing record, which – all things being equal – should be fresh in the minds of voters as they go to the polls next February. The party is also hampered by the perceived parochialism of the president, Mr. Muhammadu Buhari, a disposition which has inflamed Nigeria’s fractured federation under his watch. APC is also burdened by its choice of flag-bearer for the 2023 presidential election, in the person of Bola Ahmed Tinubu, a political juggernaut no doubt but who suffers severe reputational handicaps. Suspicion persists about his ethical antecedents, specifically about the source of his seemingly inexhaustible personal wealth. Tinubu also faces persistent questions about his personal health – a crucial concern in the succession of Buhari whose presidency has been dogged by issues of ill-health. There is concern that the president’s debilitated state has allowed secret cabals to hijack his agenda, tilting same towards extreme corruption and particularism. And there is fear of a repeat with the potential accession of Mr. Bola Tinubu, another sickish septuagenarian with impaired health and impaled morality.

In light of the ruling party’s handicaps, the main opposition party, PDP, should have no difficulty meeting the constitutional threshold for victory. After all in the 2019 presidential poll, PDP met the 25% threshold in 29 states plus FCT Abuja, although it lost the election, having secured only 41.2% of the national votes – 15 percentage points behind APC. But PDP is also disadvantaged for reneging on its zoning principle which should have allowed for a power shift to the South. The party’s decision to abandon its zoning principle is sensible for evident strategic reasons, as I argued in a previous article. But it might hurt the party in the next election. For one thing, it had led to the defection of Peter Obi, the party’s 2019 presidential running mate who hails from the South East geopolitical zone, one of PDP’s erstwhile strongholds. Mr. Obi, who has since joined the Labor Party (LP), is working up a storm on the hustings, suggesting probably that a shellacking awaits PDP in the South East in the upcoming election. PDP has also been injured by the defection – for entirely different reasons – of another party stalwart, Rabi’u Musa Kwankwaso, a former two-term governor of Kano State, who is reported to have joined the New Nigeria People’s Party (NNPP).

As for the fringe parties, the prospects are not unpropitious, but they are not commanding either. These parties performed quite poorly in the 2019 presidential election, collectively pulling in a pitiful 3% of the votes though they represented about 97% of the field (inversely, APC and PDP, which represented about 3% of the field, secured 97% of the national votes). Certainly the dynamics have changed from what they were in 2019, but not so dramatically that any of the minor parties has a chance of winning the election on its own.

All the above argues for alliance formation between sets of political parties in the lead-up to the 2023 presidential election. The dictates of game theory (and its dynamic variant, theory of moves) compel such alliances, despite the vagaries of such alliances in Nigeria’s political history. By alliances, I don’t mean strictly political party mergers which could lead to some presidential flag-bearer conceding the top slot to a different contender in the merger partner. Maybe, at this juncture in the cycle, that ship has sailed! I include all forms of strategic and tactical collaboration, from not campaigning too hard in each other’s stronghold, agreeing an armistice so to say, all the way to and including a pact for power-sharing after the election.

Let’s consider the imperative of alliance building from the perspective of game theory. The primary goal of game theory, which is widely applied in military and business strategy, is to develop an understanding of the structure of incentives that could predict behavior in complex systemic settings. As applied to politics, game theory can cover several areas including policy making, democratic participation, electoral behavior, electoral alliance and political coalitions. I will reference game theory here only in connection with electoral alliances.

I mentioned above that the political duopoly of APC and PDP has had a stranglehold on power in Nigeria, with absolute control of all the levers of power. Currently, in terms of executive leadership, APC controls the presidency along with 22 states, including North West and North Central where it controls 11 of 13 states; North East where it splits the six states evenly with PDP; the South West where it controls five of six states; the South East where it controls two of five states, and the South South where it controls just one state. The PDP controls 13 states in all, including five in its South South stronghold; five of the 19 states in the North; two in the South East; and one in the South West. It is a picture of absolute duopolistic dominance.

It is possible, however, that the political duopoly could lose some of its purchase on power in the 2023 election. The most significant factors that could induce a dip in duopolistic power, as indicated earlier, are APC’s abysmal governing record, on the one hand, and the fracturing of PDP with the departure of two party stalwarts, Peter Obi and Rabi’u Kwankwaso, on the other. These developments have changed the dynamic and competitive topography in the presidential game, moving from a two-player setting in 2019 (APC-PDP) to a four-player setting in 2023 (APC-PDP-LP-NNPP). In terms of zonal breakdown I expect, even with these developments, that the duopoly will still maintain its strongholds in the South West (APC) and South South (PDP), though not without a serious challenge by the newly envigored fringe parties. However, the duopoly will face much stronger competitive pressure in the South East and in the entire North, likely losing significant vote share to Peter Obi’s Labor Party in the South East and also a sizeable share across the North – especially in the North West – to Rabi’u Kwankwaso’s NNPP.

If these changes in the competitive landscape turn out, as expected, to be significant, we might end up in a politically fraught situation wherein neither of the two major political parties nor any of the newly vitalized fringe challengers could secure an outright majority. Instead, one of the major parties would likely pull ahead of the others with a slim plurality of the votes. The party with the plurality lead could still form a government, based on Section 134 2(a) of the 1999 Constitution (as amended), in so far as the party has secured no less than 25% of votes in each of at least two-thirds of the states and Abuja. But such would only be a minority government, which will face ominous challenges, reminiscent of the extreme instability the country faced in the First, Second and Third Republics.

The parties can prevent this outcome by forging strategic alliances to improve their electoral chances and governing ability. I envisage several possible axes of such electoral alliance, including: (i) APC overture to NNPP, wherein the major party attempts to exploit the disgruntlement of the ex-PDP Kwankwaso gang, using the latter’s reputed ground game to shore up its northern defense against probable PDP onslaught; and (ii) PDP rapprochement with the Labor Party, which could help the party to avoid total annihilation in the South East. This option now seems unfeasible, given PDP’s choice of Governor Ifeanyi Okowa of Delta State as the running mate to its flag-bearer, Atiku Abubakar. As a South South native with an Igbo ancestry, Mr. Okowa’s selection is a nuanced choice designed to help the party defend its South South stronghold whilst remaining competitive in the Igbo South East. Political leaders in the region, wary of the minoritization of Igbo politics portended by Obi’s fringe play, would welcome the choice of Okowa as the next best thing after losing the flag-bearer and running mate slots in the party. But it remains to be seen how the broader South-eastern electorate, resenting the short shrift and electrified by Peter Obi’s candidacy, might react in the end.

If these alliances are not possible, we can also think of another option, (iii) Labor Party merger or other strategic collaboration with NNPP. This is in fact being openly canvassed, even in the media.

A Labor Party/NNPP alignment is a politically feasible and also a highly rational option. We might imagine the two fringe parties currently facing – to use game theory concepts – a Prisoners’ Dilemma: each has an advantage which places it in a kind of Nash Equilibrium (or even, as an economist might say, at Pareto Optimality) wherein it might seem that they can’t improve their electoral payoffs by collaborating with one another. Peter Obi, with his lacerating message of frugality and economic recovery, is enjoying much popularity in his campaign, far more so it seems than NNPP’s Kwankwaso. But then, Obi’s Labor Party currently has not a single electoral seat to its credit, versus Kwankwaso’s NNPP which has one Senate, four House of Reps and 13 state assembly seats. Each of the two parties could press forward on its own believing it would gain nothing from a political collaboration that would require its candidate to stand down for the other. However the parties could far improve their odds against the entrenched duopoly if they could find a workable arrangement. The collaboration would enable the two parties to play competitively in both the North and South, leveraging on Obi’s personal popularity and Kwankwaso’s ground game in the North. This might in fact resolve to a dominant strategy for both parties (again to use a game theory concept), the one that maximizes their payoff whatever either of the entrenched parties does.

We thus arrive at a potential triad of electoral alliance-sets in a “cooperative” 2023 presidential election game (to use a parlance of the field). Of these, (i) and (ii) are mutually consistent while (iii) is mutually exclusive with the other possible outcomes in the triad.

The remaining question then is to consider the potential payoffs from a systemic perspective. It might be controversial, but I would argue that (i) and (ii) are the more rational choices in this regard. Either would lead to a clear majoritarian outcome and ensure that a stable government emerges from the 2023 election. If these choices prevail, the PDP/LP alliance could sail through the finishing line with a slim majority, which could be vastly improved if the party goes for a dominant strategy by moving to re-align with Kwankwaso’s NNPP. If APC, instead, deploys a similar dominant strategy by aligning with both LP and NNPP, it too could end up winning by a wide margin.

An alliance of LP and NNPP is rational but some might find it unsettling from a systemic perspective. The alliance would dilute the electoral potency of the major parties whilst being itself unable to achieve either a plurality of the national votes or the required 25% in two-thirds of the states. This is not to deny any systemic utility from an LP/NNPP alliance. There certainly could be, inhering in the possibility that it would firm up the fringe parties as a viable third option in the matrix of choices for the electorate; one that would be in a stronger position to win power through an accumulation of victories in subsequent state and federal elections.

In other words, either of the major/fringe alliance options proposed above – (i) and (ii) – would dilute duopolistic control of power but ensure systemic stability, whereas the fringe/fringe alliance – (iii) – would weaken the duopoly, positioning the fringe challengers to take power in subsequent elections. But in so doing, this option could also create systemic instability which could result in an authoritarian intervention similar to what we experienced in the earlier Republics. It is a gnawing concern I had articulated in an earlier article, framing it this way:

It is certainly unclear whether a ‘revolutionary’ outcome, if it materializes, will be accepted by the entrenched oligarchy in Nigeria. We have only to recall the ‘coup’ of June 12, 1993 when the military regime of Gen. Ibrahim Babangida annulled the legitimate election of Chief M. K. O. Abiola, on grounds which are still being debated but which certainly had to do with the threat the result posed to the prevailing political order.

Days after my piece was published, I read in the newspapers that outspoken elder statesman and former minister of aviation, Chief Mbazulike Amaechi, expressed a similar concern. The concern about a system-stressing outcome should not be seen as an attempt to preserve the status quo. Rather, it is to recognize the value of incremental change in Nigeria’s volatile ecosystem.

If the players in the upcoming election choose to act rationally, they would forge electoral alliances in any of the forms constructed above. But, of course, it remains to be seen whether or not our political players are governed by rational instincts.

We shall find out soon enough.

Perhaps the most literate analysis I’ve read in months about the current political landscape of the country.