There may be a prima facie case of aggravated infractions in the just concluded presidential election in Nigeria. However, it might be challenging to meet the high burden of proof the courts would require to overcome the need for system preservation and vacate an officially declared presidential election result.

By Chudi Okoye

Even in the separate ‘world’ press conferences they held to oppose the controversial presidential election result that INEC had just announced, the two main opposition parties could still not agree. The events were intended to showcase the opposition’s grievances and their plans to recover a supposedly stolen mandate. But even in this, the parties presented conflicting claims.

At his press event held on March 2nd, the day after the final results were announced by the electoral umpire, INEC, Peter Obi of the Labor Party (LP) – looking sombre and emotionally exhausted – declared that he had won the election and that he was heading to court to prove it. Soon after that event, the media team of the putative winning party, All Progressives Congress (APC), issued a caustic riposte – which was part dare and part prebuttal – taunting Mr. Obi and saying they would meet him in court. The complainant seemed more complaisant than the accused, though each played to their usual style: Mr. Obi understated; Tinubu’s attack dogs bristling with bravura.

For his part, the flag-bearer of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), Atiku Abubakar, whilst not at the point avouching his victory, was nonetheless hailed by his boisterous party entourage as the winner of the election. Atiku would not say affirmatively that he was headed for the courts, only that his legal team was studying the facts and that he awaited its advice.

These two candidates, PDP’s Abubakar and LP’s Obi, came the closest as first and second runners-up to Bola Tinubu, presumptive winner of the presidential election in Nigeria, which held on February 25 2023. Their parties have been the loudest in alleging irregularities in the election process, while other opposition parties have offered only murmurs of disapproval or absolute silence.

Incompetence and Alleged Collusion

The management of the 2023 presidential election was by no means a model of excellence. The easiest case that can be made against INEC (Independent National Electoral Commission) is one of gargantuan incompetence. This was seen the most in its clumsy management of techinal operations, especially in troubleshooting the glitches and snarls in its blockchain technology set up for election data storage and transmission of results. It was also revealed in the commission’s cack-handed and insensitive manner of responding to complaints from voters and opposition parties. The impassive disposition of Professor Mahmood Yakubu, INEC Chairman, amid a din of public and partisan denunciations, only added to the mounting frustration. It seemed at times as though a placid academic was leading a flaccid organization. Professor Yakubu’s deportment mirrored the notoriously blasé attitude of President Muhammadu Buhari in his current round of ruining (sorry, running) Nigeria’s affairs.

INEC’s evident incompetence and the indifference of its leadership gave vent to a vexed accusation of collusion with the ruling party, including allegations of vote suppression, voter intimidation and misallocation of ballots. These all need to be tested through an election tribunal and eventually the courts, as provided by law.

Election results are always vigorously contested in Nigeria. The First Republic saw a plethora of post-election litigation, most notably suits and countersuits involving Chief Obafemi Awolowo and Chief Samuel Akintola in the Western Region. All presidential elections since 1979, except for the 2015 election, ended up in legal contestation. Post-election litigation in Nigeria might appear reflexive but perhaps they are unavoidable in a contentious democracy where political power intersects with economic and social status, such that most elections become but an existential struggle.

The history of presidential election litigation in Nigeria is daunting, though, for any hope of easily petitioning the 2023 shambles. No presidential election petition has ever been decided in favor of a petitioner, and none has led to election annulment (except in one case, by the military). Even so, there seems to be a strong prima facie case of actionable infractions in the 2023 election praxis. At the very least, there may be a meritable case with regard to vote suppression or voter intimidation; or one based on the legal theory that the incompetence of INEC might have upended the natural outcome of the election.

The headline data pertaining to the election are quite disturbing, and they suggest a need to dig deeper to find out what happened. In the 2019 presidential election, Nigeria had a total of 82.3m registered voters and 27.3m valid votes, indicating a valid voter turnout of 33.2%. By 2023, the registered voter base had increased by a net of 11.1m (or 13.5%) to 93.5m. Still, in spite of this notable increase, valid votes in the 2023 election supposedly dropped 12.1% to 24m, giving a voter turnout of 25.7% in the election. In other words, these headline figures would have us believe that the country registered a lot more voters in 2023 but far fewer of them turned up to vote, compared to the previous election. It just doesn’t make sense, except of course if it is thought that the currency change initiative and fuel scarcity, occurring in the lead-up to the election, had a vote-depressing effect.

There’s certainly something pointing to likely misfeasance or even outright voter disenfranchisement in the management of the election. And these are litigable.

Election Litigation

As at the time of this writing, the wheels of election litigation are just beginning to turn. On March 3rd, Peter Obi of the Labor Party filed an ex parte application at the Court of Appeal sitting in the federal capital Abuja seeking access to all the sensitive materials that INEC deployed for the conduct of the February 25 presidential election. The appellate court, with Justice Joseph Ikyegh presiding, granted the application for both Obi and the PDP candidate, Atiku Abubakar, who had filed a similar application. This court will eventually sit as the Presidential Election Petition Tribunal.

We will see how the cases evolve. Awka Times contacted some legal experts to assess the chance of the election being nullified, either by the Election Appeal Tribunal or the Supreme Court. None of the lawyers would speculate on the likely outcome at this point, since no substantive case has been filed by the aggrieved parties. One lawyer, Barrister Eustace Odunze, told Awka Times: “There are a lot of video recordings showing likely infractions during the recent elections, but they have to be packaged as credible and admissible evidence in a substantive court case, and one needs to study them to be able to offer an informed opinion on the possible outcome.”

So we have to wait.

As the parties and their candidates began to prepare their petition, there was an unexpected case filed at the Supreme Court by six PDP-controlled states – namely Adamawa, Akwa-Ibom, Bayelsa, Delta, Edo and Sokoto – seeking a cancellation of the February 25 election and a nullification of Mr. Tinubu’s declaration as president-elect. The states had initiated their case on grounds of gross irregularities pertaining especially to the transmission of results. It had seemed like a deliberate legal strategy to have the states file a possibly expedited case at the apex court while the aggrieved candidates begin their own challenge with an election tribunal, as required by law (Section 132 of the Electoral Act 2022). Indeed a legal expert, Barrister (Dr.) Peter Ntephe, contacted by Awka Times, argued that this was an “interesting and novel strategy.” But he said he doubted if the states’ case would be “taken to conclusion.”

Similarly, Barrister Odunze, citing Section 232(1) of the 1999 Constitution, told Awka Times that he was unsure of the efficacy of the states approach. “I do not understand why the states have decided to go straight to the Supreme Court on a matter that should go to the election tribunals,” Odunze said. “If the Supreme Court assumes original jurisdiction and rules on this matter brought by the states against the FG, then it has effectively ousted the powers of the election tribunals.”

Shortly after these chats with Awka Times’ legal experts, news broke that the case instituted by the PDP governors had been withdrawn. Awka Times reached out to the lead counsel for the plaintiffs, Chief Mike Ozekhome SAN, to verify the news and ascertain the reasons for discontinuance. Ozekhome confirmed the discontinuance, and told Awka Times it was “because [the petition] has been overtaken by events.”

It would seem that the case was withdrawn because the actual aggrieved parties – the presidential candidates and their parties – are making headway in their own legal foray. A substantive case by the PDP governors might have complicated or even confused the legal strategy. It’s also far from certain, anyhow, that the Supreme Court would have taken up this particular case.

Prospects for Election Petition

The opposition parties may yet succeed in their election petition, but they have been far from sprightly in pursuing a legal recourse. The parties had been on the back foot throughout the crucial stage of national results tabulation. Their representatives huffed and puffed, stomping around at the national collation centre in Abuja as results were released, simultaneously complaining about the slow transmission of results from the outposts and then the over-hasty announcement of results. They also raised issues about discrepancies between the nationally declared results and field tabulations which were supposedly in their possession. Saying the process was like a “garrison operation” for a pre-determined outcome, they called for a cancellation of the whole election and demanded a do-over. They asked for INEC chairman to step aside because they’ve lost confidence in him. In all of this, however, the opposition parties appeared at that point to rely more on moral suasion to make their case than seek a forceful legal recourse. None of the parties took a purposive legal step to stop the announcement of results, even when it seemed there was reasonable ground to do so.

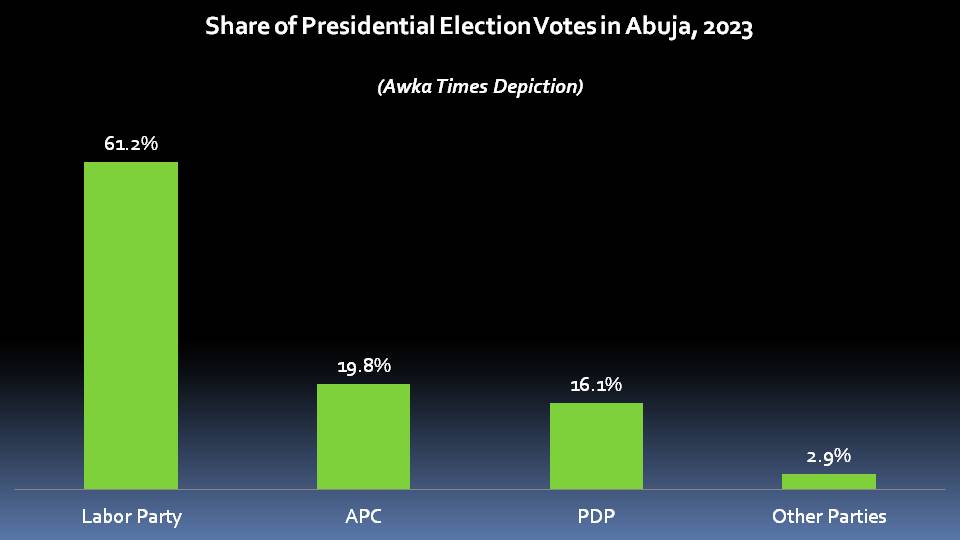

Consider, for instance, the controversy surrounding the status of Abuja, and the results for the federal capital in the 2023 election. Of the 460,071 valid votes cast in the FCT, Labor secured a commanding 61.2%; APC 19.8%; PDP 16.1%; and other parties 2.9%.

As INEC neared the end of its announcement of results at the national collation centre and it appeared that APC might have an edge, the issue of Abuja erupted. The issue centers on whether a winning party specifically requires a minimum of 25% share of votes in the federal capital, or whether the constitution construes Abuja merely as another state. Section 134(2) declares that:

“A candidate for an election to the office of President shall be deemed to have been duly elected where, there being more than two candidates for the election, he has the majority of votes cast at the election; and he has not less than one-quarter of the votes cast at the election in each of at least two-thirds of all the States in the Federation and the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja.”

One interpretation of the above provision may be that Abuja is a unique constituency and that a minimum of 25% share of FCT votes is required for a winning ticket. Yet, on a different interpretation Abuja may be construed merely as another state and not as a special case. This interpretation would seem to be supported by Section 299 which states that “the provisions of this Constitution shall apply to the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja as if it were one of the States of the Federation.” Yet, the matter is complicated by the fact that in several other regards (for instance the requirement at Section 147(3) that each state must provide a federal minister), the constitution does not accord Abuja the status of a state. There is therefore some ambiguity as to whether Abuja is a special case for the purposes of federal election.

The issue is pivotal since we’ve seen that none of the political parties, except Labor, attained the threshold of 25% in Abuja in the 2023 presidential election. As the announcement of results neared an end, APC spokespeople, showing remarkable nimbleness, suffused media outlets with a narrative that a 25% threshold in Abuja was not required. In one instance on Channels TV, a pro-APC attorney cited the petition brought by then challenger Muhammadu Buhari against President Olusegun Obasanjo in the 2003 presidential election. The attorney claimed that the issue of the status of Abuja was dispositioned in that case, and that a separate 25% threshold was not required for the FCT. But a reading of the judgment in that case by Awka Times does not indicate the issue was specifically addressed, let alone settled.

As the APC spokespeople propagated their own interpretation, clearly intending to influence both public opinion and even INEC view, I barely espied any opposition lawyer picking up the matter. The opposition parties should probably have sought a court order preventing INEC from announcing the winner of the election, pending a proper interpretation by a competent court. But, here again, they dropped the ball.

Perhaps, the opposition parties stayed their hands out of patriotic concern, mindful of the historical instance when the late Arthur Nzeribe’s Association for Better Nigeria (ABN) attempted through a court process to prevent the June 12 1993 election from holding. Failing to stop the election, ABN later secured a court order commanding the National Electoral Commission to suspend the announcement of election results. The great uncertainties attending ABN’s legal forays at the time had plunged the nation into a deep trauma of political instability and resulted, by design, in an extension of military rule. While it is commendable that the opposition may have stayed their hand out of patriotic concern, the parties might still have found a redeeming legal recourse to suspend the announcement of results without necessarily plunging the country into political chaos. After all, such concern did not stop the ruling party, APC, from taking legal action to stop the opposition parties from interfering with the announcement of results!

The same nimbleness has seen the ruling party moving fast, since INEC concluded its announcement of results and certification, to consolidate its candidate’s ‘victory’. Mindful of the logic of ‘adverse possession’, the ruling party has been busy creating “facts on the ground,” lining up stakeholders (Dangote, IBB, various constituencies, foreign governments, etc.) to show growing acceptance of Mr. Tinubu’s ‘victory’. The party is cleverly and deliberately raising the cost of any idea of nullifying the election, knowing that a conservative apex court would err on the side of system preservation, rather than hand down a ruling capable of heating up the polity. APC clearly has a nuanced understanding of game theory, more so it seems than the opposition had initially revealed.

To be fair, the opposition parties may now be becoming more planful and surefooted in their search for legal redress. I am becoming a little impressed with their approach. I still, however, detect a kink.

All through this post-election drama, I have wondered despairingly how to reconcile the Labor Party’s spectacular wins in these recent elections and the party’s demand for a cancellation of same elections based on allegations of ‘widespread fraud’. APC operatives appear as well to have alighted on this apparent contradiction. In its statement welcoming Mr. Obi’s legal challenge, the party insisted that “the 2023 election [was] one of the most transparent and peaceful elections in the history of Nigeria,” and that it was “because the process was credible [that] Mr. Obi’s Labor Party [was able] to record the over six million votes it got, contrary to pre-election forecast.”

The ruling party further asserted, in an inspired piece of prebuttal, that:

“Mr. Obi surprised bookmakers by winning in Lagos State, Nasarawa, Plateau, Delta and Edo where there are sitting governors of either the All Progressives Congress or the Peoples Democratic Party. Those governors have entrenched political machinery. That Obi won attests to the credibility of the election process. In those states, most of the sitting governors contested election to go to the Senate and lost to little known candidates of the Labor Party. The Labor Party also swept the entire five South East states under the control of either APGA, PDP or APC. We believe that the Labor Party presidential candidate contradicted himself… by suggesting that the election was only credible in states and places his party won.”

APC operatives also zeroed in on what could be a vulnerability, if ignored, in building Obi’s legal case. We know that the Labor Party had been able only to submit names of polling agents in 134,874 of the 176,606 polling units, and that it had only 4,859 collection agents which amounted to half the number for each of the major parties. It would be tough for Labor, which is now supposedly crowd-sourcing polling data, to aggregate credible and admissible evidence from polling units where it had had no official representation. APC’s spokespeople had picked up on this seeming deficiency, arguing that Mr. Obi “will have to convince the court with his allegation of rigging in over 40,000 polling units across the country, especially in North West and North East, where his party had no party agents and did not sign result sheets as required by law.”

It is a strong argument, no question. But this is not to say that APC itself is in an unassailable position. The party has gone on record with its own allegations of fraud and other malpractices in the 2023 election, just as the opposition parties have claimed. Whilst proclaiming on the one hand that the 2023 election was properly conducted, the party also claims on the other hand to have “evidence of voters suppression, intimidation and harassment in South East, especially of those who came out to vote for our party.”

This claim has prompted a reaction from the opposition PDP. A statement by the office of the PDP presidential candidate argues that APC’s “claim that there was massive rigging in the southeast and that the APC will be challenging the votes in that region validates our position that this election was fraught with irregularities. This is the reason we are seeking the cancellation of the results.”

We are thus in a somewhat unpredictable situation. The ruling party seems to be agreeing with the opposition parties’ assertion that the presidential election of February 25 2023 was deeply flawed. Yet, proving the allegations on either side might be a huge challenge, especially to the degree of clarity that would be required to overcome the residual need for political stability and system preservation.

All told, there would seem to be only a slight chance, though it is not improbable, that the election tribunal or the Supreme Court will cancel the election and order a re-run.