By Chudi Okoye

We are at this moment more than midway through the Holy Week in Christendom, a period requiring of observant Christians that they engage in fasting and abstinence, along with meditation and prayer, as we re-enact the passion of Christ and hope to rise with him symbolically on Resurrection Sunday. This moment, especially the Easter Triduum (comprising the three “high holy days” of the Christian faith), is inarguably the most important in the liturgical year or Christian calendar.

For me, as a cradle Christian (born into Catholicism, served as an altar boy and Block Rosary convener in my hometown, Awka), this is a moment for deep reflection, though I admit to a wobbly adult observance. I often, in this holiest of Christian seasons, ponder some of the deeper mysteries and greater controversies of our religion. At Easter last year, for instance, I proposed a possible rehabilitation of Judas Iscariot, the notorious apostle who’s generally – but mistakenly and unfairly in my view – taken to have betrayed Jesus.

Following that rather daring foray, which appeared to have been well-received (many readers told me they enjoyed it), I wish this year to take up another ‘hot’ topic, one relating to the central institution of this solemn season: prayer. As we move towards the end of the Holy Week, I wish briefly to probe, not merely the metaphysics of our Paschal rogations, but also the physics of prayer in broader terms.

What is prayer, and what actually transpires when we engage in the sacrament of prayer?

Let’s begin with the basics. There have been, over the ages, some wonderfully poetic definitions of prayer. For St. John Vianney, the 18th/19th century French Catholic priest canonized in 1925, “prayer is the inner bath of love into which the soul plunges itself.” For St. Thérèse of Lisieux, a 19th century French Catholic nun also canonized in 1925, “prayer is a surge of the heart; it is a simple look turned toward heaven, a cry of recognition and of love, embracing both trial and joy.” What’s perhaps considered the classic definition of prayer comes from St. John of Damascus, an Arab Christian monk born around 675 AD and declared a Doctor of the Church in 1890. For him, “prayer is the raising of one’s mind and heart to God or the requesting of good things from God.”

Going from sacred to secular sources, prayer has been defined as “an invocation or act that seeks to activate a rapport with an object of worship through deliberate communication; an act of supplication or intercession directed towards a deity or a deified ancestor.” Prayer is communion with God, the sharing or exchanging of our intimate thoughts and feelings with Him (it could be some other deity, but for the purpose of this piece, let’s just focus on the Christian God). It is communication with God, typically enacted through adoration or worship, by praising God, by confessing our sin before Him, thanking Him and asking Him for our needs and desires. Some traditions hold that the object of prayer is not to change the will of God, but to secure for ourselves and for others the blessings that God is already willing to grant, for which we have to plead as grace, not moral desert.

From these definitions, we get a clear sense of prayer essentially as metaphysics; nonetheless, being a form of communication, it must also be considered as physics. As an act of communication, involving the transmission or supposed exchange of information, prayer takes different forms in different spiritual traditions: from simple or complicated gestures to spoken or written words in the form of formal creedal statements or spontaneous utterances; from songs and hymns to chants and incantations; and from all these to various forms of spiritual meditation. But whatever the mode or medium, the act of praying implies a kind of communication with the supernatural – with God specifically; it is a transmission or an exchange of information. Prayer follows the typical transmission model of communication, complete with its source, transmitter, channel, receiver, destination, and not to forget, noise – including cultural, psychological and semantic noise!

Given all this, the question arises: if prayer is a form of communication or information transmitted from one node to another (a packet which must be encoded at source, transmitted through channels disturbed by various forms of noise, received and finally decoded at the destination), how fast does it travel and how long does it take to reach its destination? And what form must our prayer take to achieve the greatest velocity: as sound wave, thought, or something else?

To answer these questions, let us deal first with the question of communication or information transmission speed. Let us consider prayer as spoken word or chant, transmitted as sound wave. As we know from physics, under standard conditions (assuming dry air at 20 °C or 68 °F), the speed of sound is 343 metres per second (about 0.213 miles or 0.343 km per second; which is 767 mph or 1,234.4 km/h).

Is this then the utmost velocity of our uttered prayers, the top speed at which our spoken supplications ascend to God in heaven?

It is important here, for context, to compare the speed of sound (the putative velocity of our spoken prayers) to the speed of light. We focus on the speed of light because it is currently the ultimate speed limit in the universe (all superluminal or faster-than-light [FTL] travel is purely conjectural). The speed of light is 299,792,458 metres per second (which approximates to 186,282 miles or 299,792 km per second; that is 670.6 million mph or 1,079.3 million km/h).

In other words, light travels more than 874,000 times faster than sound! Whereas light travels 186,282 miles in one second, sound takes almost five seconds (4.695 seconds) to travel just one mile.

If prayer as sound wave is slower than the speed of light, what then to say about prayer as thought? Is thought faster than photon?

Unlike sound and light, there is no known direct measurement yet for the speed of thought. Thoughts are sparks of cognition constantly flitting through our minds as conscious beings. We can think of the speed of thought, on one level, as the rate at which information is processed and transmitted within the brain. This varies significantly within or between individuals, depending on factors such as the complexity of the thought process, the emotional state of the individual doing the thinking or meditation, differences in individual cognitive abilities, the external stimuli, and so on. Thinking can be zipping fast, occurring within milliseconds in certain circumstances, or they can drag into minutes and hours of contemplation. In general, researchers measure thought indirectly through reaction time, using imaging techniques like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electroencephalography (EEG) to glimpse which areas of the nervous system light up during different thought processes. Researchers agree that thoughts, as electrochemical signals, can be swift, but definitely not as swift as the speed of light.

There is some complexity about the speed of thought across space-time when we get into the quantum realm, beyond classical physics. In quantum mechanics, particles supposedly defy classical rules, such that, through what is known as quantum entanglement, information can instantaneously pass between two entangled particles even if separated by vast distances. This is still an evolving field of modern physics. But researchers think that here again thoughts, though potentially swift, are not light-speed swift.

So then, consider this: if neither sound nor thought in their propagation is as fast as light, how much time is required for our prayers, as sound wave or thought, to traverse the vast expanse of space to reach heaven, the abode of God which must be the ultimate destination in our prayer-information transmission model? Consider that the diameter of the observable universe is about 93 billion light-years, and that the distance from Earth to the edge of the observable universe is 46 billion light-years. Now, as I pointed out earlier, the speed of light is 186,282 miles (299,792 km) per second, which translates to 5.88 trillion miles (9.46 trillion km) per year. If we put these two figures together – the distance from Earth to the edge of the observable universe and the distance light travels in a year – we get a little over 270 billion trillion miles (270 sextillion or 270^21 miles) as the distance from Earth to the edge of the observable universe. The actual figure, to write it out in full, is 270,480,000,000,000,000,000,000 miles. This is the distance light travels to reach the edge of the observable universe.

Now, consider this: If heaven, the putative destination of our prayers, lies somewhere beyond the edge of the universe, how much longer would our prayers, as sound wave or thought (thus, traveling at much slower speed than light) take to reach it? The answer is obvious; moreso in the case of our uttered prayers, since there’s presumably no air to propagate them as sound across the vast emptiness of space.

There is of course some uncertainty as to where exactly ‘heaven’ is located; and it is unclear if indeed God resides only in the heavenly realm or is everywhere immanent. The Bible and Christian (as well as other religious) traditions present a somewhat confusing theology about the divine realm. The Bible suggests that God is omnipresent (see, for instance: Jeremiah 23:23-24, Psalm 139:7-10 and Proverbs 15:3), a sense implied both in the doctrine of divine immanence and in Baruch Spinoza’s pantheism. It is also evinced in the pandeism of Moritz Lazarus and Heymann Steinthal. This would suggest that our prayers – deployed as waves of sound or thought – do not need to travel great distances through cosmic space to reach God. He is here, immanent in all manifestations of nature, and therefore close to us.

But the same Bible also proposes the idea of divine transcendence, a panentheistic view suggesting that, even though we can find His imprints in nature, God Himself resides in a heavenly abode well-beyond our physical universe (see, for instance: Genesis 28:12, Isaiah 40:22, 1 Kings 8:27, Acts 7:49, Psalm 33:13-14, Psalm 97:9 and Psalm 115:2-3). Paul, writing in 2 Corinthians 12:2, spoke of Christ being taken up to the “third heaven”, which has been interpreted as a place beyond the atmosphere and outer space.

On this view, which is also well-established in religious cosmology, it would seem that our prayers have quite a distance to travel to reach God, his abode being, presumably, far beyond our physical domain. There is even a hint of this in the incipit of the Lord’s Prayer, a key Christian prayer said in two of the canonical gospels (Matthew and Luke) to have been taught by Jesus: “Our Father who art in heaven…” (“Nna anyi no n’Enu Igwe”, in Igbo language).

If, on this theological construct, God resides in a celestial realm far removed from our earthly domain, and if therefore our prayers have a ways to travel to reach Him, what might be our most expeditious way to pray? Is it through our sometimes reverent and other times muddled thoughts, or through our sometimes solemn and other times noisy supplications?

We have seen that sound and thought do not travel nearly as fast as light. But is there a way to convert our prayers into particles of light (Albert Einstein’s photon), so they can travel at the greatest cosmic speed to reach God?

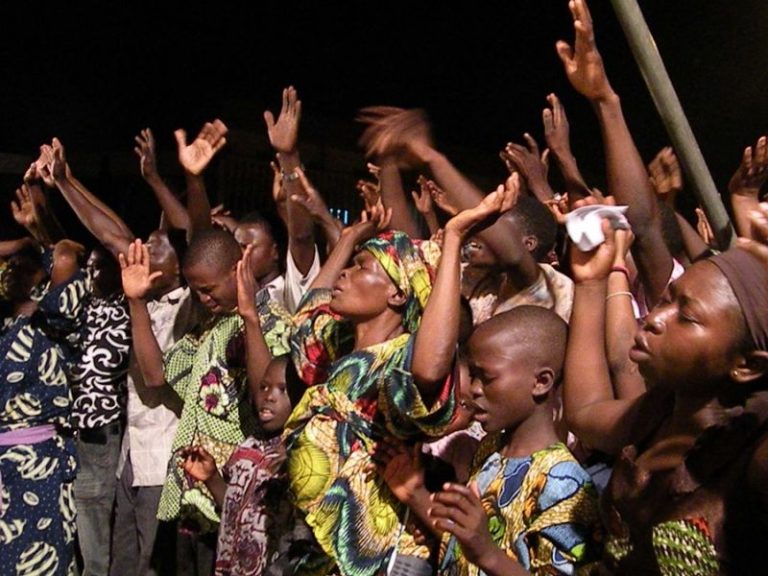

Indeed there is! It is through our deeds. Our prayers get to God the quickest, not merely in what we think or say, though these are important, but in what we do. It is for this reason, I suppose, that Jesus criticized the loud, performative prayers of the Pharisees (Matthew 6:5), a trait unfortunately all too common in contemporary worship. It is probably why Jesus said in John 8:12 that he is “the light of the world,” and why he also said in Matthew 5:16: “let your light shine before others, that they may see your good deeds and glorify your Father in heaven.”

It is why we are told in 1 John 1:5-6 that “God is light, in him there is no darkness at all,” and that “if we claim to have fellowship with Him and yet walk in the darkness, we lie and do not live out the truth.”

It is what underpins the parable of the lamp under a bushel, found in Matthew 5:14–15, Mark 4:21–25 and Luke 8:16–18, and in the non-canonical Gospel of Thomas (Saying 33).

Our most fervent thoughts or most prayerful utterances, travelling through the cosmic expanse, cannot reach God as quickly as the light we emit through our purposeful deeds.

This, I think, is the lesson we must learn when we contemplate, not just the metaphysics but the physics of prayer, especially in this Paschal period. If God is immanent in nature and is in us, then contemplative prayer or spiritual meditation might be the quickest way to reach Him. But if God is transcendent, abiding in a heavenly realm far removed from us, then prayer as sound is inferior to prayer as the light emitted by our purposeful deeds.

Happy Easter, everyone!