After a dogged 30-year pursuit of the Nigerian presidency which so far has proved unsuccessful, Atiku Abubakar, who has had an illustrious political career otherwise, might now consider giving it a rest and working instead for the larger goal of Igbo presidential accession, to achieve his abiding dream of more intimately unifying the country.

By Chudi Okoye

You could conjure up varied homophones of his name, and they would all resonate in meaning. There is, for instance, “Attacus” – a genus of butterfly-like moths which, though beautiful to behold, is considered a pest because it can damage plant life as voracious caterpillar; leave irksome residue when it flaps its wide wings; and even trigger human allergies if allowed to infest. On the other hand, there have been historical figures of some renown named “Atticus”, among them a philosopher, a rhetorician and even a Christian martyr. Also, who can forget the fictional “Atticus Finch”, the fierce activist lawyer considered the greatest hero of American cinema and even a model of integrity in legal circles for his feisty but ultimately failed defense of a black man wrongly accused of rape in the novel, To Kill a Mockingbird. And yet, in Yoruba language, “a ti kú” means “we are dead”!

Every element of this homophonic pastiche, to some degree, is evinced in the manner by which our own “Atiku” Abubakar has projected himself and prosecuted his case in the 2023 presidential election dispute.

There he was on 30th October, presenting his studied response four days after the Supreme Court’s ruling on his election petition, offering the nation what could well be (though no one can really say) his last stand.

On this day, Atiku had on a serene, sky-blue kaftan and matching cap; and he wore his typically impassive demeanor, though his impassioned words revealed a seething, deep-seated anger. His incandescent mood was unmistakable even as he quietly and dignifiedly laid into the courts, his political bête noire – President Bola Tinubu, and the electoral umpire.

Waziri Atiku Abubakar had had much the same mien earlier on 7th September, a day after the Presidential Election Petitions Tribunal (PEPT) delivered its own judgment on the petitions brought by several opposition parties and their candidates to challenge the official results of the 25th February presidential election.

Seized as he seemed by a surge of moral indignation, and projecting as he did the image of a determined political crusader, Atiku proclaimed at his post-judgment press parley that he would “continue to struggle” for Nigerian democracy for the rest of his life, even though, as he put it, “for me and my party this phase of our work is done.”

No one can say, if they were fair, that the man didn’t try. Hardened perhaps by his previous political battles, not least against a self-entrenching military regime and later against the unconstitutional third-term agenda of a wily president and army general under whom he had served, Atiku emerged in the 2023 election legal contests as the fiercest challenger, and has inflicted by far the deepest wound on Tinubu’s presidency. He inveighed publicly and cuttingly against the courts and the electoral umpire, even as a complaisant Peter Obi, the other major protagonist in the post-election palaver, perhaps wisely (given his rabid support base) played a disciplined game of “politics without bitterness” (a la Waziri Ibrahim of blessed memory). Atiku put Tinubu through a crushing wringer, stubbornly pursuing a legal recourse – even beyond our shores – to uncover evidence from Tinubu’s past which revealed a man with a deeply flawed moral character. It was mainly on account of Atiku’s exertions that I wrote as follows in a recent prose poem, in oblique reference to Tinubu:

“Our hassled leader is lurking in his tasseled chambers, haunted by his tousled past and by opponents with whom he tussled.”

Atiku Abubakar has made sure that Bola Ahmed Tinubu is politically damaged.

But if Atiku laid waste to Tinubu’s political persona in the process of election litigation, what about Atiku himself? How does he come off in the whole election saga?

Not particularly well, I would say, despite the image of a principled political crusader that he sought to project in the 2023 election controversies. A parsing of his statements after the Supreme Court ruling against previous stances shows a measure of incoherence, shape-shifting and perhaps opportunism.

Questionable Recommendations

Consider, for a start, Atiku’s proposal, contained in his post-judgment press statement, that “we must make electronic voting and collation of results mandatory.” This is a somewhat surprising – if sensible – suggestion, coming from Atiku. Didn’t the man argue, through his lawyers for the 2023 election litigation, that electronic collation and transmission of results was already mandated by law? His suggestion here seems to confirm the opposing parties’ argument to the contrary, which was upheld by the courts. If Atiku’s reading of the statutes has changed in light of the courts’ ruling, he should simply have said so, and then on that basis, propose the mandation of electronic processes as he has done. His proposal here contradicts his earlier legal stance; yet he carried on as if the courts had been wrong in dismissing his argument.

Atiku also made another landmark suggestion which seems to me rather poorly argued. He said “we must provide that all litigation arising from a disputed election must be concluded before the inauguration of a winner,” noting that “[t]he current time frame between elections and inauguration of winners is inadequate to dispense with election litigations.” This is a suggestion I’ve heard elsewhere, and it sounds quite sensible, until you begin to peel it apart.

First, to an attentive observer, this would seem to be an unwitting admission that the petitioners, arguably constrained by time, had not been able to marshal the evidence they needed to prove their allegations of widespread malpractice and other infringements in the election. It was much the same point (which I cited in a previous article) made by one of Peter Obi’s lead counsels, Prof. Awa Kalu (SAN), in which he mentioned the near impossibility of assembling sufficient evidence, within the short window of time allowed by law, to back up the opposition’s case. As a reminder, Section 285(5) of the 1999 constitution as well as Section 132(7) and Paragraphs 4(5) to 4(6) of the 1st Schedule of the 2022 Electoral Act stipulate that parties wishing to file election petitions must do so, along with their list of witnesses and the latter’s depositions, no later than 21 days after the declaration of results. This is, undoubtedly, a tough requirement. But in arguing the point, both Atiku and Kalu appear to affirm the validity of the PEPT’s judgment that the petitioners adduced insufficient evidence to support their claims. This, in turn questions the pervasive narrative of a compromised bench pushed by Atiku and other figures in the opposition.

Beyond even this important point, one also wonders if Atiku, in proposing a delay to the inauguration of a new administration pending the legal resolution of election disputes, had considered the ramifications. Currently, our laws allow for a maximum of 21 days to file petitions, as noted above; 180 days after that for the appeal court – as court of first instance – to consider the petitions and render judgment ((Section 285(6) of the constitution and Section 132( 8) of the Electoral Act); and 60 days thereafter for the Supreme Court to deliver judgment on any appeal(s) resulting from the appeal court’s ruling (Section 285(7) of the constitution and Section 132(9) of the Electoral Act). This all adds up, on the outside, to a total of 261 days – nearly nine months after election results should have been declared!

Pray, is Atiku Abubakar suggesting that we delay the inauguration of a new government for more than nine months after an election has been called? Who would run the country during the prolonged interregnum? Should we formally extend the tenure of the incumbent president whose governing mandate is ending? Or should we perhaps install the Senate president as acting president, being next in line after the elected incumbent and his vice? If the latter, should we then change the laws, since Section 146(2) of the constitution allows a Senate president to act as national president for no more than three months?

Clearly, extending the time allowed for the resolution of election disputes, as Atiku recommends, would create a lot of confusion. To achieve his goal of a longer lead time for disputes, we must have an interregnum between administrations or start the election process much earlier. Either option is a recipe for political instability.

It isn’t clear if Atiku considered all these ramifications. It is possible the man merely meant that we should extend the 21-day window for the filing of petitions and submittal of evidence and witnesses, and not necessarily that we should extend the overall timeframe for dispute adjudication. But if that is what he meant, he should have said so, and then we can debate the merit of that suggestion. As it is, he merely said we should allow time for all election litigation to be settled before inauguration takes place. Clearly, in making this perfunctory suggestion, Atiku did not seem to have considered all the implications.

More Questionable Suggestions

There is also Atiku’s suggestion that we should switch to a majority voting standard. As he put it, “in order to ensure popular mandate and real representation, we must move to require a candidate for President to earn 50% +1 of the valid votes cast, failing which a run-off between the top two candidates will be held.” This is clearly a dig at Tinubu’s supposed victory, secured with only 36.6% of the votes cast in the February election.

The 1999 constitution provides for both majority and plurality voting. It requires at Section 134(1)(a) that a candidate must win a “majority of votes” where there are only two contestants, and at Section 134(2)(a) that they secure the “highest number of votes” if there are more than two. Atiku’s recommendation of a majority vote, whatever the number of candidates, is well-intended I’m sure. But it will constrict political choices and rigidify our two-party dominant system which we have just begun to shake up with the 2023 election results. Would Peter Obi, for instance, have migrated to the Labour Party, and thus created an unprecedented third-party momentum, if confronted with the calculus of having to win over 50% of the votes? Certainly not! Atiku’s suggestion here is unsuited to our complex and politically diverse landscape.

Of all the suggestions made by Alhaji Atiku Abubakar, the most radical – and also the most curious because it seems self-implicating – is his proposal that “we… move to a single six-year term for President [which should] be rotated among the six geo-political zones.” Atiku based this proposal on the recommendation of the 1995 Constitutional Conference, in which the former vice-president had participated.

Fancy that! Atiku Abubakar now rooting for zoning and rotational presidency!

Pray, where was this commitment last year, in the lead-up to the primary election of Atiku’s party, the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), when Atiku and his northern acolytes machinated his victory in a most brutal fashion, in the process frustrating southern members of the party who had demanded a rotational concession to the South based on the promise of the party’s own constitution? The greatest frustration of course was felt in the South East, a region which had supported the party in the most lopsided manner and has suffered for it with the accession of the All Progressives Congress (APC). It was this very issue that created the rupture within the PDP that led to the party’s defeat in the February presidential election.

I had written about this issue long before the election, in a July 2022 article titled “Atiku Abubakar versus the South East: Political Usurpation and Electoral Consequences in 2023.” I opened that article declaring that “Atiku Abubakar has a South East problem,” and went on to say that “it is almost certain that he faces an upset in that geopolitical zone in the coming presidential election….” I concluded the article arguing that the PDP had “made poor choices in the composition of its 2023 presidential election ticket,” and that “the mistake could cost it the election.”

This was in July 2022, seven months before the presidential election. Unfortunately, events turned out as I had predicted. Atiku’s primary election machinations and violation of his party’s zoning principle contributed in no small way to PDP’s loss of an election it should won handily, allowing Tinubu and his party to scrape through with only a plurality. This is the inescapable fact of the 2023 presidential election, whatever else might be said about electoral corruption.

Atiku, 2027 and the Igbo Question

Atiku’s frustration of the South East political goals did not start with the 2023 presidential election. There are many who believe he was deeply involved in efforts that frustrated Dr. Alex Ekwueme’s presidential outing in 1998 and 2003; surely a sad history for a man who moved the earth to build the party into a national juggernaut.

Atiku’s relationship with the South East is certainly complicated. He was once married to an Igbo woman. He has had deep ties in the upper tiers of the Igbo political class. Atiku has been running for Nigerian presidency since 1993, and on the three occasions when he snagged his party’s nomination, he picked a running mate of Igbo extraction. Yet, in the lead-up to the 2023 election when his party’s zoning principle should have been leveraged in favor of a southern flag-bearer, preferably someone of Igbo extraction, Atiku and his acolytes orchestrated the process in aid of his own selfish goal.

One could, perhaps justifiably, pick bones with Atiku and point to what I might call a soft bigotry of inferior concessions, perceivable in his apparent preference of Igbo for running mate but obstructing the legitimate Igbo aspiration to the top job. However, though that case could be made with merit, we need not dwell on it now. With Atiku now presumably in the twilight of his political career, it should be possible for him to make amends and dispense his remaining political capital in the service of helping to achieve the overarching Igbo presidential aspiration.

The 2027 presidential election seems to me an opportune moment to do this. Atiku would be aged well past 80 by that time. Although being an octogenarian has not proved an impediment to presidential ambitions in some countries (see, for instance, Joe Biden in the US), Nigeria, with its myriad governance problems and its weak democratic institutions, does need an energetic president – one who is relatively young and healthy. We saw what the debilitations of age and health did to the Buhari presidency, allowing diverse hidden forces to hijack his agenda and bend same to a privatized and primordial will. It turned the Buhari presidency into an unmitigated disaster. The same appears now to be shaping up with the presidency of Bola Tinubu, who claims to be in his early 70s but clearly betrays the ravages of a more advanced age, noticeable physically but also intimated by occasional signs of a cognitive decline.

There should be absolutely no question of Atiku Abubakar running for the Nigerian presidency in 2027. Instead, to prove what he told Arise TV last year about his “desire to unify the country,” Atiku should now work with the Igbo political class to achieve the goal of Igbo presidency in 2027 – and, in this way, avoid a brutal zoning logic that will put off the prospect to 2039.

The forces are well aligned for 2027. Though there’s always the advantage of incumbency in Nigerian politics, Bola Tinubu can (and should be) defeated if he seeks re-election, what with his so far listless and unbridled presidency and the baggage of ignominy he carries from the controversial 2023 election, resulting in no small measure from the forensic efforts of Atiku Abubakar himself.

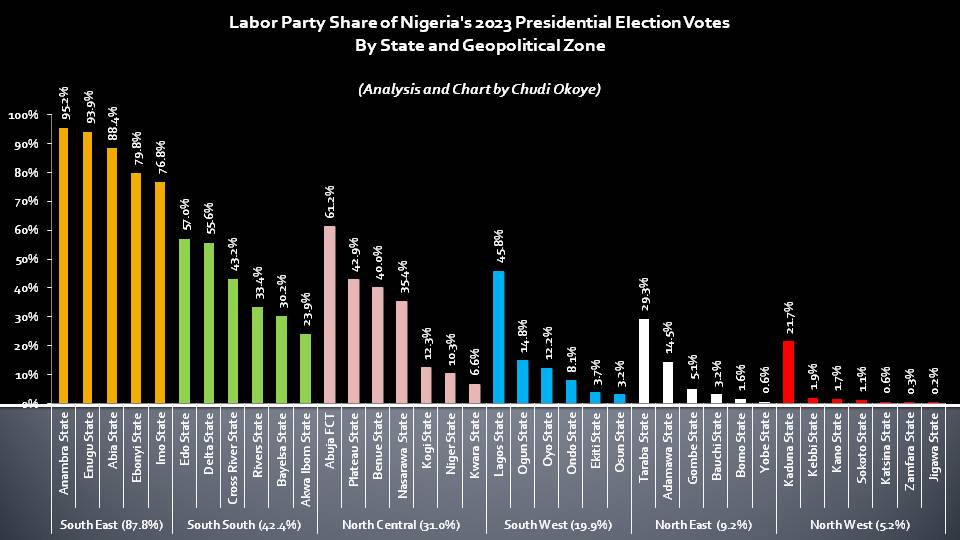

In addition to this, Peter Obi acquitted himself very well in 2023, achieving in a very short time what no fringe-party candidate had done since the dawn of the Fourth Republic. In a mere matter of months, he moved a moribund political party into the political map, winning 25.4% of the votes as officially accounted, securing 25% in 16 states and carrying the federal capital territory, Abuja, plus 11 of the states (including a Lagos State once governed by Tinubu). Beyond his native South East, Obi performed quite well in several other regions, nabbing 42.4% of votes in the South South, 31.0% in North Central, and 19.9% in the South West. It was only in Buhari’s North West zone and Atiku’s North East that Obi fell short, two resistant zones he couldn’t penetrate probably for want of time and strong local allies. Even in these two zones, however, there were some breakthroughs, with Obi winning 29.3% in Taraba State (North East) and 21.7% in Kaduna State (North West).

It is a performance with promises of improvement if the dynamic of 2023 can be sustained. All that is needed is for the South-easterners to coalesce around a common agenda in the nation’s interest, and to take their message of national integration into the furthest reaches of the country.

An Atiku that’s now advanced in age may not be able to carry off another presidential foray for himself in 2027. But he can certainly work towards the integrative agenda of producing a Nigerian president of Igbo extraction in his lifetime. In this way he might truly acquire for himself the revered status of a Nigerian statesman, and might even end up in the rarefied company of the esteemed Chief Obafemi Awolowo, as a great president Nigeria never had.