Peter Obi won the Nigerian presidential election of February 2023. Probably not so in the statistical sense of ballot share, a matter which is being litigated, but with regard to the quotient of gained prestige and political stature. When assessed against other candidates in the election, Obi is the undisputed ‘Man of the Match’. This final part of a trilogy on the presidential election (see Pt. 1 and Pt. 2) examines the Obi phenomenon and what it might portend for Nigerian politics if consolidated.

By Chudi Okoye

I know – yes, I do! – that right now in Nigeria we are in a season of hyperboles and high-octane emotions. So, dear reader, I will understand if you espied the title of this essay and instinctively sneered at it. ‘Black Swan’ and ‘Tocqueville Effect’? What the heck are those?, you might have asked. ‘Revolutionary moment’ in Nigeria? Give me a break!, you might have gasped. Well, before you contemn or condemn the title, come along let’s unpack the phenomenon to which it alludes.

First, to ensure we are all on the same page, let’s start with concept definitions. If you aren’t familiar with what’s known as ‘Black Swan Theory’, it’s a concept – popularized by Nassim Taleb, a Lebanese-American writer and risk statistician – which explores the logic of random, unexpected or highly improbable events with high-impact outcomes. Mr. Taleb – a former options trader who has taught the Science of Uncertainty and also Risk Engineering at several universities – codified this theory across several books, the best-known of which are: Fooled by Randomness (2005); The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable (2007); and Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (2012).

Fascinating titles, right? You bet! The British Sunday Times once described Taleb’s Black Swan as one of the twelve most influential books since World War 2. The guy’s got game!

I have provided details of Mr. Taleb’s titles as an early hint of where I am taking this essay on the Peter Obi phenomenon.

Now, let’s turn to the ‘Tocqueville Effect’, or what’s sometimes called the ‘Tocqueville Paradox’. In my most recent Awka Times article on the outcome of the February 2023 presidential election in Nigeria, I coined the phrase “revolution of rising palpitations” to depict the roiling reactions attending the Independent National Electoral Commission’s management of the election and its now controverted results. I’d coined this phrase as a play on the well-known expression, revolution of rising expectations, invented (back in 1949) by the American diplomat, Harlan Cleveland.

Cleveland formulated this phrase to describe what had come to be known in Social Science as the Tocqueville Paradox which holds that social revolutions are born, often not out of deteriorating conditions and extreme immiseration of the lower classes – as Karl Marx and his followers have argued, but rather from growing frustrations in society caused by rising expectations of improved living conditions and upward mobility, themselves triggered by initial incidences of social progress. In other words, the more social conditions improve the greater the expectation from benefiting classes and the more intolerant they are of any reversal of social change.

This theory of revolution derives from the work of Marx’s contemporary, the 19th century French aristocrat and diplomat, Alexis de Tocqueville, who had studied the social conditions and revolutionary upheavals in America and France and published his findings in books that are now classics of Social Science: Democracy in America (1835, 1840) and The Old Regime and the Revolution (1856). From Tocqueville’s sociology of revolution has emerged a theory that stands Marxism on its head: the claim that revolutionary impulse is driven not so much by the deterioration of social conditions but by the initial improvement of them (which raises standards and expectations) and subsequent reversals (which breed widespread frustration).

With the foregoing, let’s now delve into the Obi phenomenon.

Obi vs. the Big Two

As soon as political party primaries commenced in this electoral cycle, I – like some other analysts – began to write about the Obi phenomenon. Though not awestruck like his fervent followers (yeah, a la Rudyard Kipling, some of us kept our heads while others seemed to be losing theirs!), I have written several articles in this magazine graphing Obi’s political ascent, describing what I called “the Peter Obi Insurgency” in one early piece and, onomatopoeically, “the Pitter-Patter of Petermentum” in another.

Although some newspaper columnists came late to the realization (one once portrayed a presidential field led by “two and a half” candidates, Obi being the “half”), Obi’s campaign did take off with an early tailwind and, showing remarkable agility, he kept building momentum right up to the eve of polling day. I wrote in my recent essay that “Peter Obi is the undisputed star of the 2023 general elections.” Indeed he is. I would add even, without equivocation, that he is the ultimate ‘winner’ of the presidential election, the ‘Man of the Match’.

I don’t mean by this that he polled the highest statistical votes. Obi claims of course that he did, and there’s not an iota of doubt about it among his posse of peppy supporters. But the matter is now being litigated. We will see where empirical evidence leads.

I mean instead that Obi won the election in terms of the quotient of gained prestige and political stature. I argue that Obi garnered the most and grew the mostest among all candidates in this presidential election cycle. I will discuss the details. But let’s look first, as baseline, at how the two other leading candidates tracked in this election, ignoring the rump (the other 15 contestants) in the long-tailed lineup.

Take the putative winner of the election, Bola Tinubu of the ruling party, All Progressives Congress (APC). The dude may have won, as INEC claims, but he comes away from this shoddy affair utterly discredited. For a start, his party APC lost a whopping 6.4m votes and dropped 19 percentage points in 2023 versus its vote share in 2019. Tinubu depleted his party and he will govern, if the courts confirm his ‘victory’, with a truly questionable mandate. Of the 93.5m registered voters and 87.2m of them who collected their PVCs, only about 24m assumedly voted, of whom just over a third, 36.6%, cast their votes for the ruling party’s candidate. As an even grimmer statistic, the 8.8m that voted for Tinubu represent only 9.4% of registered voters and something like 4.1% of the total population. This would be about the most impaired mandate of any president since the Second Republic. It trumps only by a few percentage points the 33.7% of votes garnered by Alhaji Shehu Shagari in the 1979 presidential election in which the latter, anyway, had to face some juggernauts of Nigerian politics, including Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe, Chief Obafemi Awolowo, Malam Aminu Kano and Alhaji Waziri Ibrahim. Every other winning ticket since then outperformed Mr. Tinubu’s squeaker in this election.

But it isn’t only the stats that startle about Mr. Tinubu. There’s also the image thing; the character thing; the reputation factor. It’s not just the niggling concern about Tinubu’s health, which is no mean matter by itself: look how sick Nigeria became under a sickly Muhammadu Buhari. It’s also the unshakable stench that pervades this man’s personal reputation. There’s financial scandal, with no one really certain about the source of Tinubu’s stupendous wealth. There’s drug scandal, which now has the world sniggering about a Nigeria soon to be ruled by a shady fellow implicated in drug trafficking. With his antecedents and the manner of his emergence as president, Tinubu will confirm the worst stereotypes about Sleazy Nigeria. He will sweep into Aso Rock trailing a cloud of moral turpitude which may not lift until he leaves office. Tinubu may be reputed as a political tactician but there’s just a foulness of form and fame that follows him which even the presidency cannot deodorize. It seeps through his allegedly porous pants into his political base and carries into all the crannies of his political universe. Tinubu, alas, will represent the ultimate cartoonification of the Nigerian presidency.

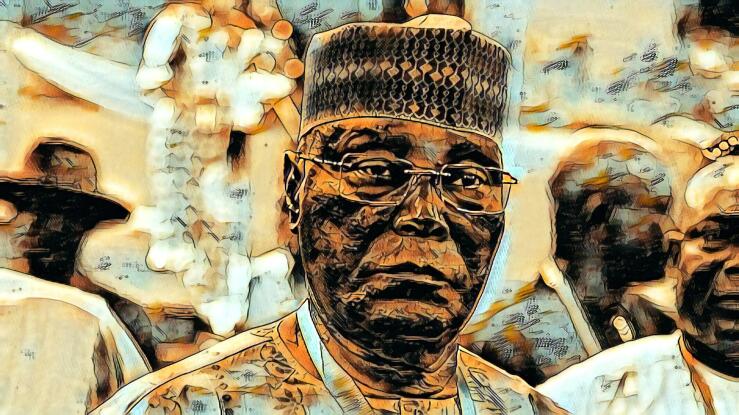

Turning to Mr. Atiku Abubakar, there’s nothing after this election but a flotsam, the wreckage of a once promising political career tarnished by repeated defeats, corruption scandals and the stigma of betrayal. He’ll be remembered not just as the man who made it impossible to evict a hollowed ruling party but also someone whose ambition filibustered the possibility of a president of Igbo extraction and, thus, a chance finally to exorcize the demons of the Civil War. Abubakar’s political denouement is both sad and sickening. He leaves the stage with his party, the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) – under which he served as VP and whose ticket he has led in two elections – hugely shrunken and deeply fractured. It is a most unedifying legacy.

And so we arrive at Peter Obi.

The Obi Phenomenon

I am on record for questioning the exorbitant claims about Obi’s record as governor of Anambra State. I am from the state, so I know the truth and have not swallowed some of the fictions peddled by some of Obi’s supporters – and sometimes by Obi himself. This is not to say that Obi didn’t perform well as governor. He did. It just isn’t as outstanding a record as is often portrayed.

Obi also earns a slap on the wrist for his rapid flight from PDP when, it seems, he sensed some force fields against his prospects in the party’s primary. Obi’s exit certainly contributed to the fragmentation of PDP, an unfortunate reality which redounded to APC’s electoral advantage, as I argue in an earlier piece.

Obi might share in the blame for the consequence of PDP fragmentation, but, unlike Atiku Abubakar, he has a redeeming card in what he accomplished in this election from the platform of his destination party.

There are two ways to calibrate what Obi has accomplished – one, by the numbers; the other, normative.

The numbers are just staggering. Let’s recall where the Labor Party stood at the time Obi decided to join it after decamping from PDP. The party was nothing and it was nowhere. It had not a single seat anywhere, not at national or sub-national level. It did once boast a governorship and a House of Reps seat, but at the onset of the 2023 election cycle the party had nothing and it existed only on paper. The status of Labor as an electoral force is best depicted by its performance in the 2019 presidential election: of the 27.3m valid votes cast in that election, Labor scooped up all of 5,074 votes; that is, 0.02% of the total.

Yet, within just one election cycle, with Peter Obi’s diligent electioneering – and without merging with any other party – Labor went from that incredible state of absolute nothingness to being, now, a notable ‘Third Force’ in Nigerian politics. In the 2023 presidential election, Labor scooped up 6.1m votes, representing 25.4% of total valid votes cast in the election (PDP – a previous 16-year incumbent which fielded a veteran of five earlier presidential elections as its flag-bearer and which still controlled many governing and legislative seats – secured only an equivalent 6.98m votes or 29.1%). Labor carried the federal capital Abuja (where Buhari resides!), winning a whopping 61.2% of the votes there, which meant no other party approached the 25% threshold in the FCT (an achievement which might be critical in the ensuing election litigation). Labor also carried 11 states, and won 25% in a total of 16 states (APC and PDP carried 12 states apiece). The states carried by Labor included Lagos, a state Tinubu had governed for two terms and which he supposedly still controlled as political godfather. Furthermore, on current tally of the National Assembly elections, Labor has won seven Senate and 34 House of Representatives seats. And permutations are that the party is poised for significant wins in the upcoming state assembly and governorship elections.

There is no other way to put it: this is a monumental change in political fortunes for the Labor Party. And it’s down, simply, to a single factor: the capture of the party by Peter Obi.

The achievement is even more compelling when you consider other fallouts from these electoral facts. Obi has now emerged, indisputably, as a national political figure – from just four years ago when he was merely Atiku Abubakar’s nondescript running mate who barely registered on the Richter scale of national politics. He now has a fervent political following: a discrete, trans-regional, supra-generational, multi-demographic following with a strong affinitive identity and intense loyalty attaching exclusively to the person of Obi, not necessarily to his party. The remarkable thing is that although Obi is in his 60s, he has emerged as the avatar of generational change and symbol of post-primordial politics in Nigeria. There are still some sentiments attaching to Peter Obi as perhaps the embodiment of the hope for a geopolitical correction which will see a person of South East extraction catapulted to the apex of power in Nigeria. But this sentiment is not at all primordial in its aspiration; it is merely a yearning by South-easterners for re-integration into the grand diagram of power in Nigeria. Nigeria itself needs this correction, perhaps more so than its seekers!

This is a truly remarkable achievement, the more so – going back to our opening theoretical metaphor – for its Black Swan effect. The story of black swans is that no one believed they existed; it had been thought, in the West at least, that all swans were white. All that changed in 1697 when the Dutch explorer, Willem de Vlamingh, discovered black swans in Australia. This is the story of Peter Obi and the Labor Party. The party was totally inconspicuous in the arena of politics. And its nouveau venu, Obi, though better-known than the party, had been merely governor of a mid-sized state in the smallest geopolitical enclave in the country, one described as a “dot” by a certain dolt in Aso Rock. Sure, Obi occasionally popped up in national consciousness as something of a public intellectual grappling with sundry national issues. But he was just that, an occasional public intellectual without a discernible power base. Until Obi’s campaign took flight, few could have anticipated his incarnation as a canny political operator now with a proto-movement which could, if nurtured, disrupt the fundamentals of Nigerian politics.

Up until this election cycle, it had been believed – and our election statistics affirmed it – that fringe parties were merely an accounting fiction in Nigerian politics, without electoral force or efficacy. Though we had 18 registered political parties, Nigeria was really a de facto two-party state dominated by shifting coalitions of the political elites. Now, this election has started what could upend such presumption about Nigerian politics.

It might be thought that the Third-Force breakthrough engendered in this year’s elections is ephemeral; that it is merely a temporary aberration and that soon – perhaps by the next election cycle – we will witness a ‘regression to the mean’, as we say in my analytics profession: a reversion to the rigid orthodoxies of Nigerian politics. Perhaps. But this is where our second theoretical reference kicks in: the thing about the Tocqueville Effect. Hitherto, the rigidities of Nigerian politics discountenanced the deep currents of social change taking place in the country. There’s a youth bulge in Nigeria’s demographic structure which creates a peculiar impulse to change and a Weltanschauung totally unaccommodated in the insular praxis of our politics. Now, with Obi’s ascendancy, this impulse and its worldview may finally have found a mainstream political outlet and, if nurtured may compel its ethic of progressive change upon our politics.

Much depends on what Obi decides to make of his political career from here on out. If he settles in his mind that his departure from PDP constituted a revolutionary break with establishmentarian politics, and if he feels he has the stamina for it, he might want to nurture his proto-movement into a permanent force in Nigerian politics. Sometime last year, I wrote a poem titled “Rise Up!” to celebrate Obi’s exit from PDP and the dawn of his new mission. In it, I wrote:

The old party’s primary was his epiphany

To stop palling around with men of infamy

He felt a great vocation newly beckoning

Which he must give the fullest reckoning

I hope Peter Obi fixates on that mission, and that he can enlarge his vision to embrace its full revolutionary potential. Modifying the old, well-known Edmund Burke saw about good and evil, I’d say the only thing necessary for evil to triumph is not merely that good men do nothing, as the Irish statesman and philosopher said, but that they bungle what good they get to do. St. Augustine said to build a tower that will pierce the clouds, one has first to lay a foundation of humility. Obi is humility personified, at least going by his public image; a Black Swan that may become a real force in Nigerian politics.

As a social scientist and journalist, I can’t be partial to any partisan tendency. But, for the sake of our much-abused country, I will be rooting for Obi, if he pursues a revolutionary agenda.